I've made a couple posts about herbicide resistant weeds but I thought today would be a good time to go back to the basics for a moment. Occasionally, there is some confusion about the definitions of a "resistant" weed versus a "tolerant" weed. Although on one hand a definition seems like a pretty basic starting point, there was considerable debate about how to define herbicide resistance. The Weed Science Society of America (WSSA) [http://www.wssa.net] eventually settled on the following:

"Herbicide resistance is the inherited ability of a plant to survive and reproduce following exposure to a dose of herbicide normally lethal to the wild type. In a plant, resistance may be naturally occurring or induced by such techniques as genetic engineering or selection of variants produced by tissue culture or mutagenesis." From a practical standpoint, if you think "We’ve never gotten dependable control of this weed with this herbicide…” - that is probably best described as "tolerance".

"Herbicide tolerance is the inherent ability of a species to survive and reproduce after herbicide treatment. This implies that there was no selection or genetic manipulation to make the plant tolerant; it is naturally tolerant." Practically, if you think "We used to be able to control this weed with this treatment but it doesn’t seem to work anymore…” - that may be "resistance".

Causes of Resistance:

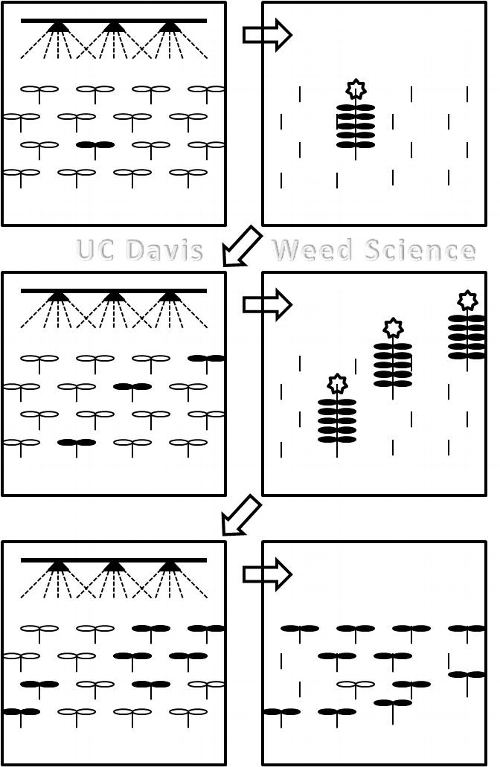

Herbicide resistance in weeds is an evolutionary process and is due in large part to selection with herbicides – usually repeated use of the same herbicide or products with the same mode of action. A common misconception is that herbicides “cause” resistance; however, herbicide-resistance is usually due instead to naturally occurring mutations in the plant’s genetic structure. On a population level, organisms occasionally have slight mutations in their genetics; some of these are lethal to the individual (ie. a plant that does not produce chlorophyll), some are beneficial (ie. drought tolerance) and some are neutral (no observable effect on biochemical function). Occasionally, a one of these chance mutations affects the target site of an herbicide such that the herbicide does not affect the new biotype. Similarly, mutations can affect other plant processes in a way that reduces the plant’s exposure to the herbicide due to reduced uptake or translocation or through more rapid detoxification. Whatever the cause, under continued “selection pressure” with the herbicide, resistant plants are not controlled and their progeny can build up in the population. Depending on the initial frequency in the population and the reproductive ability of the weed, it may take several generations until the resistance problem becomes apparent (see cartoon figure).

Weed Shifts:

Another issue commonly confused with resistance is weed shifts in response to control practices. Weed populations are usually mixed and composed of a number of different species in any given field. Weed management practices (any practice, not just herbicides) will have a slightly different effect on the individual species in the population mixture. Over time, continued use of one practice can lead to the population being dominated by one species or group of species. Obviously, herbicides can lead to this - one classic example is the shift from mainly broadleaf weeds in cereal grains being largely replaced by grass weeds after the introduction of 2,4-D. This herbicide selectively removed broadleaf weeds from grass crops but did not affect grass weeds - the weed population became dominated by grasses. Another example is a shift from annual weeds to more problems with perennial weeds in no-till farming systems. Perennial and biennial weeds often become more problematic when tillage is reduced or eliminated. Similarly, selective control such as mowing can lead to weed populations shifting to species that complete their lifecycle before normal mowing operations (winter annuals) or to prostrate or decumbant species (ie, knotweeds and purslane) instead of those with upright growth habits.

Superweeds:

Finally, I thought I'd close this post by commenting on the term "superweeds" that is commonly used in the media when discussing herbicide resistant weeds. I would argue that this is really an inaccurate way to describe (or sensationalize) the problem with herbicide resistant weeds. For the most part, herbicide resistant weed biotypes are no more competitive, reproductively fit, ecologically damaging etc than their susceptible counterparts. Of course they can be economically damaging where they are allowed to reach epidemic proportions but no more so than an uncontrolled suscepetible population would be. Effective weed management based on field scouting and an understanding of selection pressure and weed biology can be used to reduce the impacts of resistant weeds.

There is a quote attributed to Albert Einstein suggesting that "the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results". If your weed management strategy isn't working as expected, don't keep doing the same thing and expect different results. It may be time to reevaluate, troubleshoot, and implement different weed control tactics before the problem gets out of hand.