Posts Tagged: Shermain Hardesty

Cottage food law not the answer to small-farm woes

The UC small farm program held a series of two-day workshops around California to outline the provisions of the new law. Shermain Hardesty, UC Cooperative Extension specialist, was the coordinator and an instructor for the series. The class was popular, but many of the farming participants found that the letter of the law tended to hinder their creativity rather than open new business avenues.

Hardesty said the Homemade Food Act (AB 1616) was designed to, among other things, help farming families take their surplus produce and make dried products, jams, jellies and butters. However, the California Department of Public Health is requiring cottage food operators to do all of their processing in their home kitchen, to comply with the Statutory Provisions Related to Sanitary and Preparation Requirements for Cottage Food Operations (Excerpts from the California Health and Safety (H&S Code, including H&S 113980 Requirements for Food), specifically, the CDPH requires that cottage food operators comply with the following operational requirements:

"All food contact surfaces, equipment, and utensils used for the preparation, packaging, or handling of any cottage food products shall be washed, rinsed, and sanitized before each use. All food preparation and food and equipment storage areas shall be maintained free of rodents and insects."

Cutting fruit and laying it in the sun to dry, for example, is not permitted. For jams and jellies, the law stipulates sugar-to-fruit ratios that require more sugar than fruit. For some cooks, the rules defeat the unique character of their homemade, gourmet products.

“I really try not to put a lot of sugar in my jellies. I want it to taste like fruit,” said farmer Annie Main, who took the UC class.

Main and her husband Jeff run an organic fruit, vegetable, flower and herb operation on 20 acres in the Capay Valley of Yolo County.

“I've been doing value-added for 20 years,” Main said. “In the '90s, I started making jams and jellies in a rented certified kitchen. But it's a trek to get labor, jars, supplies and fruit to the restaurant kitchen after hours and then work till midnight. We thought with the new law, I could do it in my own kitchen, which would be fabulous.”

However, she found that the rules of the law are so restrictive as to be prohibitive.

“Farmers in the class were asked whether the law extended their ability for economic return on their products. Every single one shook their heads,” Main said. “The new law doesn't help us at all.”

Hardesty said there may be other options for these producers to process and sell their foods. She is planning to offer another class this fall, “Cottage Food Plus,” to help growers find workable mechanisms for selling their food.

“They may be able to use a co-packer to do the processing or a commercial kitchen or become registered as a processing food facility,” Hardesty said.

Creativity helps small-scale farmers survive

To survive as a small-scale farmer, it may not be enough to merely grow food. With most people eating food grown by very large commercial agricultural enterprises, small farmers can attract sales with some creativity and a personal touch, reported Gosia Wozniacka of the Associated Press.

Farm operators generated $10 billion in 2007 from farm-related activities other than crop or livestock wholesale, an increase of nearly 80 percent from 2002, the article said.

For perspective on what is known as value-added agriculture, Wozniacka spoke to Shermain Hardesty, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Davis. Hardesty said value-added products are "a way to have a product to sell year-round, even during winter months."

Examples of value-added products are jams and jellies, farm stays, workshops and U-pick operations.

"It reinforces farmers' connection to consumers," Hardesty said. "And by getting involved in marketing their identities, they can expand their profitability."

Providing the public a 'farm experience' can help small-scale farmers stay afloat.

Media gets UC input for stories on unconventional farming

Reporters sought UC Cooperative Extension expertise for recent articles about unusual farming efforts in two parts of California.

Fresno Bee reporter Robert Rodriguez covered the story of sisters in their early 20s who have settled on their dad's Laton alfalfa farm after he suffered complications from a black widow bite. The young women purchased chickens on a whim and began producing specialty eggs under the brand name "Just Got Laid."

Rodriguez spoke to Shermain Hardesty, UCCE specialist in the Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics at UC Davis, about trends in cottage farming.

"The timing is right for operators who can make a connection with consumers," Hardesty said. "People will support that."

Sacramento Bee reporter Edward Ortiz wrote about a return to dry-land farming in the Central Valley, with examples of farmers opting out of irrigation in producing particularly tasty apricots, wine grapes and tomatoes.

UC experts, however, commented on the difficulties associated with dry-land production in the valley.

"Dry farming would be a hard life because you're at the whim of the rains," said Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis. "It would have to be a fairly small-scale farm, and in some cases, it would be a good road to poverty."

For the Modesto Bee version of the story, Roger Duncan, UC Cooperative Extension advisor in Stanislaus County, told the reporter dry-land farming doesn't appear to be catching on locally.

Duncan said wine grape growers might withhold irrigation early in the growing season to control leaf growth and improve fruit quality, but water is still needed later on. He noted that the valley in the 19th century was widely planted with wheat that relied on rainfall. The boom ended when irrigation allowed diverse fruits, vegetables and other crops to be grown.

Workshops to prepare growers for food safety

For consumers, the effects of food safety practices can seem simple, though critically important: You’re either sick from the food you eat or you’re not.

But for producers, food safety comes in many shades of risk at many critical points in their business operations: water testing, worker hygiene, harvest techniques, postharvest cooling and storage, previous land use, wildlife and more.

To help small-scale farmers better plan for food safety concerns, several UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors are being trained in food safety audits and are planning food safety workshops. The project is led by Shermain Hardesty and Richard Molinar of the Small Farm Program, with funding from the UC Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The group is beginning to offer workshops for farmers in eight regions of California.

Why now?

New FDA regulations are being developed for the Food Safety Modernization Act that will affect food producers, among others. The act includes an exemption for farms whose annual sales were less than $500,000 on average during the last three years, with the majority of their product sold directly to consumers, farmers markets and restaurants within the state or within a 275-mile radius.

"Even though it exempts many small farmers, the Food Safety Modernization Act says the exempt producers would still need to comply with any food safety regulations from state and local governments," Hardesty said.

Trevor Suslow, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in food safety at UC Davis, has said that the FDA can withdraw the exemption with cause.

“Whether or not the exemption will hold, I think, is incumbent on everybody,” he said.

He expects the regulations will be implemented in tiers, with smaller farms having three years to comply once the regulations are final.

Even without regulations in place, more buyers — including packinghouses, retailers and at least one certified organic distributor — are requiring farmers to meet food safety standards. Insurance companies are also, in some instances, cancelling policies or hiking rates for small farmers who have not documented their food safety practices, according to Hardesty.

Many farmers who work with large packinghouses, sell to major distributors or are members of a commodity-specific commission have already established their food safety practices to adhere to standards of their industries.

But smaller farmers who grow multiple crops or who aren't part of a commission may still be looking for food safety guidance, which these workshops aim to provide.

"Most of the growers I work with are exempt, but even so, they are very concerned about how it will affect them," said Cindy Fake, one of the UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors who is part of the project and works in Placer and Nevada counties. "There is a lot of awareness of what is coming down the line."

Food safety basics

The workshops will include presentations about food safety as it relates to regulatory and business trends, previous land use, workers, water, wildlife, waste, soils, harvest, transportation, traceability and farm mapping. What should a farmer do with all this information?

“First and foremost, farmers should have some sort of food safety manual, a written food safety manual for their individual farm,” explained Richard Molinar, UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor in Fresno County. “And then if they want or need to be certified, that’s a second step with a third-party auditor.”

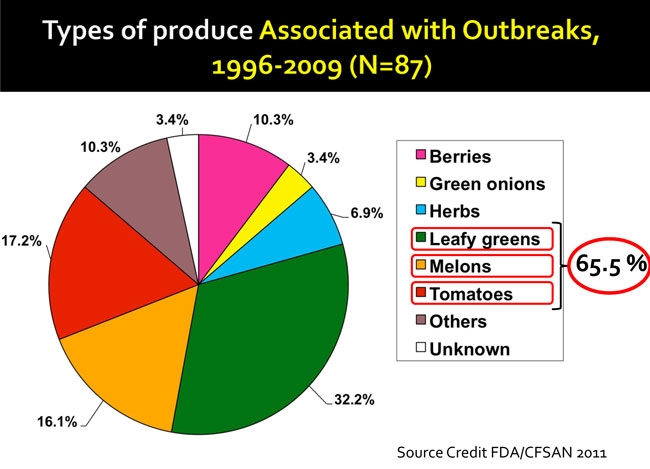

In his session, Suslow examined the link between fresh produce, outbreaks and illnesses. Leafy greens, melons and tomatoes have been associated with a combined 65 percent of produce-related outbreaks, between 1996 and 2009.

He listed key areas of food safety for all farming and shipping:

- Water: pre-harvest and postharvest

- Workers: hygiene and training

- Waste: manure and compost

- Wildlife: intrusion and fecal

- Recordkeeping

- Traceability

Food safety programs, he explained, depend on multiple hurdles to help prevent biological, chemical and physical hazards from entering food, surviving, growing and persisting.

Cold chain management is one critical aspect of postharvest food safety. Bacteria can double in a very short period of time if cold chain management is neglected.

“In just a few hours, you can go from something that won’t affect most of us to something that would make you sick,” Suslow said.

Workshops

Food safety workshops for this project will be held in multiple regions around the state. The first such workshop, scheduled for April 12 in Santa Rosa, has already sold out.

Registration is available for the next food safety workshop, May 3 in Stockton. The workshop is free to attend, though pre-registration is required.

Additional workshops will be planned by UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors participating in the project, who are located in Lake, Sonoma, San Joaquin, Placer, Nevada, Santa Clara, Fresno, Ventura and San Diego counties.

All food safety workshops associated with this project will be included on the Small Farm Program's calendar as well.

Some additional resources, recommended by farm advisors on this project:

- Creating a food safety manual:

- California small farm food safety manual from UC Cooperative Extension

- On Farm Food Safety project is part of Familyfarmed.org and can help farmers create a customized food safety plan. Suslow was a technical advisor to this project, along with a national team of stakeholders and specialists.

- Good Agricultural Practices Food Safety Plan template from Penn State Extension

- Books from UC ANR:

- Small Farm Handbook includes a chapter on postharvest handling and safety of perishable crops

- Organic Vegetable Production Manual includes a chapter on postharvest handling for organic vegetable crops

- Free publications from UC authors (PDFs)

- Postharvest chlorination

- Water Disinfection: A practical approach to calculating dose values for preharvest and postharvest applications

- Postharvest Handling for Organic Crops

Back to the newsletter: Find more Small Farm News articles from our Vol 1. 2012 edition.

Growers can find strength - and profit - in numbers

Together, growers can offer enough volume or range of crops to attract retailers, foodservice outlets or institutions that might be out of reach for each individual farm.

Stern included comments from a wide variety of experts in her article, including marketing professionals, small-scale farmers, a co-op manager and Shermain Hardesty, UC Cooperative Extension specialist at UC Davis with expertise in agricultural economics.

She told the reporter that someone — ideally one of the producers — needs to take charge of the collaborative marketing program, but finding someone with the time, aptitude and inclination may mean hiring a manager.

Do farm subsidies cause obesity?

Christopher Shea, Wall Street Journal

The link between agricultural subsidies and obesity is highly tenuous, according to a UC study that analyzed the effects of price supports on diet. The study, authored by Bradley Rickard, Abigail Okrent and Julian Alston, says if all subsidies were magically erased — including trade barriers — the typical American adult would actually respond by eating about 3,000 to 3,900 additional calories a year.

Alston is an agricultural economics professor at UC Davis, Richard is with Cornell, Okrent is a Ph.D. candidate at UC Davis.