Food safety: GAPs manual, mock audits prepare farmers

There was a surprise waiting for the food safety auditor when he looked around for signs of wildlife, though the farmer had told him his farm didn’t have any rodent problems. Under a bin were some tunnels, one of which contained a dead mouse.

“You don’t want an inspector to find a dead mouse 6 feet from your strawberries,” said Richard Molinar, UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor, in recounting the story. “First you need to think about everything in the field, but then you also have to be aware of burrows in your neighbor’s field.”

Surprises like these could lose a farmer points — or even mean failure — in a food safety audit. But this was just a test, a mock audit to help farmers better prepare their own food safety plans.

Background

Focus on food safety — through education, market demand and legislation — has been ramping up since 2007, after E. coli contamination of spinach grown in Salinas. In January of this year, the Food Safety Modernization Act was signed into law, which includes an exemption for growers with annual sales of less than $500,000, if the majority of sales are made directly to local consumers, restaurants or stores. And in late April, USDA formally proposed a national leafy greens marketing agreement similar to the California LGMA already in place.

Though some small farms are exempt from food safety legislation or major marketing agreements, their buyers may still require they adopt and adhere to a food safety plan.

In September 2010 Molinar heard a local packinghouse that contracts with many small-scale growers in Fresno County was requiring all their farmers have a food safety manual.

“And it’s not just [this grower-packer-shipper] and their buyers. It’s many other retailers, wholesalers and processors too,” Molinar said. “It’s really buyer- and consumer-driven, so [for now] it doesn’t matter what FDA or USDA comes up with. If the consumer or the buyer wants to see a food safety program, the farmers and the packers have to come up with it.”

Developing a manual

Since 2007, Molinar has held meetings to educate growers abut food safety, and in 2009 he began working with Jennifer Sowerwine and Christy Getz, both of UC Berkeley, to develop a food safety manual that could help farmers get started.

The manual provides a framework for a food safety plan, with information about standard operating procedures, worker training and recordkeeping. The manual must be personalized to the farm, implemented and documented.

“We wanted something really basic that we could use for small-scale farmers,” Molinar said. “Larger, corporate farms can afford to hire a person to do this for them and have a more complex document. We’re trying to come up with something very simple, but even this one still requires some paperwork and filing documents in the correct part of a binder with envelopes and receipts.”

The manual also requires some decision-making on the part of the farmer, most likely informed by demands of potential buyers.

“Right now it’s so new that for most of the crops — except for leafy greens or fresh-market tomatoes — there aren’t specific guidelines or standards,” he said. But having a basic food safety manual in place for the farm is fairly easy and keeps the farm competitive.

Mock audits

Certain buyers or groups may require that farmers have their food safety practices audited. Third-party food safety audits can attest to whether the farm is adhering to its food safety manual and can identify when the plan, related actions or documentation fall short of good agricultural practices (GAPs).

Though private firms can conduct these audits, the California Department of Food and Agriculture also performs verification audits in relation to food safety.

To help educate the region’s farmers, CDFA agreed to do some mock audits on Fresno area farms to help prepare farmers. A handful of mock audits have been conducted with small groups attending to observe.

“Farmers right now do not have to be audited by a third party — that’s up to the buyer — but they should at least have some sort of food safety manual,” Molinar said. “Even though third-party audits aren’t required, we thought it was a good way for farmers to start learning about food safety and look at some of the questions that would be asked.”

Lessons learned from the mock audits can save time, money and embarrassment down the road.

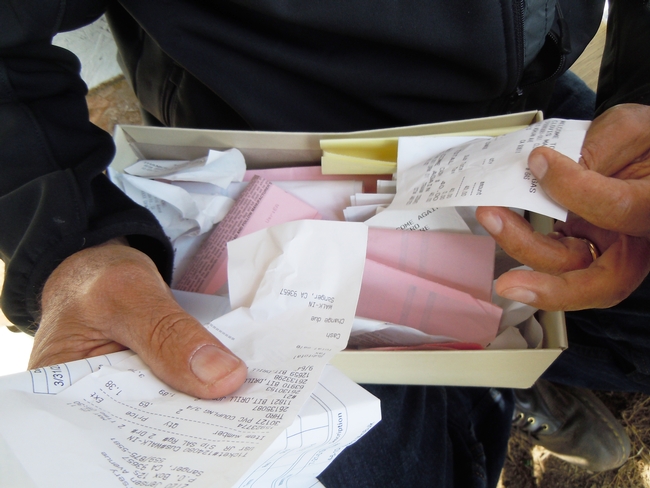

“In the first audit we did, the farmer pulled out a shoebox of receipts, and they weren’t organized. So the auditor is thumbing through the box to look for the receipt,” Molinar said. “You need to be organized because you’re paying the auditor by the hour.”

Increasing market competitiveness

Having a food safety plan in place can certainly improve safety and reduce risk, but it can also make it easier to sell to new buyers who are interested in food safety documentation.

“The main goal is to have our farmers in Fresno — and statewide — ahead of the game in food safety, so that buyers and consumers can be assured that their food is safe,” Molinar said. “It will give our farmers a marketing advantage if they have a food safety program in place because that’s what buyers and consumers want to see.”

Read the rest of Small Farm News, Vol. 1 2011.