Posts Tagged: Vol. 1 2012

Workshops to prepare growers for food safety

For consumers, the effects of food safety practices can seem simple, though critically important: You’re either sick from the food you eat or you’re not.

But for producers, food safety comes in many shades of risk at many critical points in their business operations: water testing, worker hygiene, harvest techniques, postharvest cooling and storage, previous land use, wildlife and more.

To help small-scale farmers better plan for food safety concerns, several UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors are being trained in food safety audits and are planning food safety workshops. The project is led by Shermain Hardesty and Richard Molinar of the Small Farm Program, with funding from the UC Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The group is beginning to offer workshops for farmers in eight regions of California.

Why now?

New FDA regulations are being developed for the Food Safety Modernization Act that will affect food producers, among others. The act includes an exemption for farms whose annual sales were less than $500,000 on average during the last three years, with the majority of their product sold directly to consumers, farmers markets and restaurants within the state or within a 275-mile radius.

"Even though it exempts many small farmers, the Food Safety Modernization Act says the exempt producers would still need to comply with any food safety regulations from state and local governments," Hardesty said.

Trevor Suslow, UC Cooperative Extension specialist in food safety at UC Davis, has said that the FDA can withdraw the exemption with cause.

“Whether or not the exemption will hold, I think, is incumbent on everybody,” he said.

He expects the regulations will be implemented in tiers, with smaller farms having three years to comply once the regulations are final.

Even without regulations in place, more buyers — including packinghouses, retailers and at least one certified organic distributor — are requiring farmers to meet food safety standards. Insurance companies are also, in some instances, cancelling policies or hiking rates for small farmers who have not documented their food safety practices, according to Hardesty.

Many farmers who work with large packinghouses, sell to major distributors or are members of a commodity-specific commission have already established their food safety practices to adhere to standards of their industries.

But smaller farmers who grow multiple crops or who aren't part of a commission may still be looking for food safety guidance, which these workshops aim to provide.

"Most of the growers I work with are exempt, but even so, they are very concerned about how it will affect them," said Cindy Fake, one of the UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors who is part of the project and works in Placer and Nevada counties. "There is a lot of awareness of what is coming down the line."

Food safety basics

The workshops will include presentations about food safety as it relates to regulatory and business trends, previous land use, workers, water, wildlife, waste, soils, harvest, transportation, traceability and farm mapping. What should a farmer do with all this information?

“First and foremost, farmers should have some sort of food safety manual, a written food safety manual for their individual farm,” explained Richard Molinar, UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor in Fresno County. “And then if they want or need to be certified, that’s a second step with a third-party auditor.”

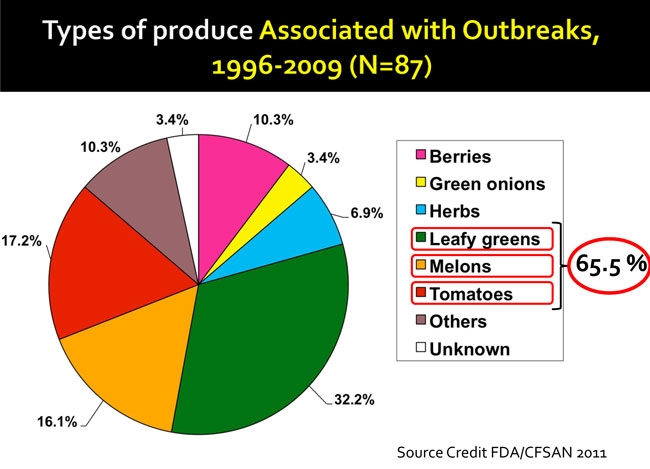

In his session, Suslow examined the link between fresh produce, outbreaks and illnesses. Leafy greens, melons and tomatoes have been associated with a combined 65 percent of produce-related outbreaks, between 1996 and 2009.

He listed key areas of food safety for all farming and shipping:

- Water: pre-harvest and postharvest

- Workers: hygiene and training

- Waste: manure and compost

- Wildlife: intrusion and fecal

- Recordkeeping

- Traceability

Food safety programs, he explained, depend on multiple hurdles to help prevent biological, chemical and physical hazards from entering food, surviving, growing and persisting.

Cold chain management is one critical aspect of postharvest food safety. Bacteria can double in a very short period of time if cold chain management is neglected.

“In just a few hours, you can go from something that won’t affect most of us to something that would make you sick,” Suslow said.

Workshops

Food safety workshops for this project will be held in multiple regions around the state. The first such workshop, scheduled for April 12 in Santa Rosa, has already sold out.

Registration is available for the next food safety workshop, May 3 in Stockton. The workshop is free to attend, though pre-registration is required.

Additional workshops will be planned by UC Cooperative Extension farm advisors participating in the project, who are located in Lake, Sonoma, San Joaquin, Placer, Nevada, Santa Clara, Fresno, Ventura and San Diego counties.

All food safety workshops associated with this project will be included on the Small Farm Program's calendar as well.

Some additional resources, recommended by farm advisors on this project:

- Creating a food safety manual:

- California small farm food safety manual from UC Cooperative Extension

- On Farm Food Safety project is part of Familyfarmed.org and can help farmers create a customized food safety plan. Suslow was a technical advisor to this project, along with a national team of stakeholders and specialists.

- Good Agricultural Practices Food Safety Plan template from Penn State Extension

- Books from UC ANR:

- Small Farm Handbook includes a chapter on postharvest handling and safety of perishable crops

- Organic Vegetable Production Manual includes a chapter on postharvest handling for organic vegetable crops

- Free publications from UC authors (PDFs)

- Postharvest chlorination

- Water Disinfection: A practical approach to calculating dose values for preharvest and postharvest applications

- Postharvest Handling for Organic Crops

Back to the newsletter: Find more Small Farm News articles from our Vol 1. 2012 edition.

Building statewide support for California agritourism

At a recent statewide summit, California agritourism leaders overwhelmingly agreed that a statewide organization would be a major step toward improving agritourism support in the California.

Statewide associations can develop and share resources and provide a unified voice for a growing agritourism industry. Many other states have developed statewide agritourism associations which help foster collaboration among county and state agencies, agritourism operators, local agritourism associations, tourism professionals and other supporters and partners.

Local organizations, local promotions, local regulations

California agritourism is primarily organized, regulated and promoted at the county or local level, resulting in a diversity of local organizational structures and branding efforts. The county-based regulatory system also leads to major differences in permitting, regulations and fee structures throughout the state.

Although some local agritourism associations are successful in drawing tourists to their regions and benefit their members by offering networking, training and marketing opportunities, many groups struggle with lack of organizational and marketing expertise and minimal financial or staff support. Many individual agritourism operators and potential operators in California are in regions with no supportive trade or marketing organization. Collaboration among local agritourism associations and county staff responsible for regulating or developing agritourism is weak, with wide disparities in regulations and agritourism support between different counties.

California's 58 counties bear the primary responsibility for permitting and regulating agritourism operations on agricultural land within their boundaries. The counties often struggle with creating allowances and ease of permitting for agritourism businesses, while ensuring that agritourism is a supplemental (rather than primary) activity on a commercial farm or ranch. Regulations also must ensure that agricultural production and local residents are not adversely affected by tourism.

Each county’s staff must research the general plans and zoning ordinances of other counties when updating their own, but there is no central clearinghouse for this information. Interpretations and enforcement of state-level environmental health and direct marketing regulations, which affect agritourism enterprises, also vary widely among the counties.

At least sixteen other states have organized statewide agritourism associations, most of these involving partnerships between state departments of agriculture or tourism, university extension and agritourism operators. At least 23 states have enacted statutes that address agritourism, varying from liability protections for agritourism operators to tax credits to zoning requirements. Many other states include agritourism promotion and resources for operators on state department of agriculture or tourism websites.

Views from the summit

At the statewide agritourism summit, organized by the UC Small Farm Program and UC Cooperative Extension Nov. 4 in Stockton, the approximately 120 participants talked together in regional breakout groups, including one group representing statewide interests. Six of the seven groups agreed that a statewide agritourism organization would be an important part of building better support for California agritourism.

- Facilitate the sharing of resources, ideas and best practices among regional and local agritourism organizations

- Create a resource clearinghouse of county policies, ordinances, regulations, fee structures, procedures, guides and general plan language related to agritourism; and foster more communication about these issues among county planners and stakeholders

- Participate in state-level discussions and planning committees about issues relating to agritourism and advocate for the interests of agritourism operators in statewide regulatory changes. Issues mentioned by summit participants as needing change included:

- Easing direct marketing laws to allow cooperative marketing or reselling of local produce with exemptions from strict food facility environmental health regulations

- Limited liability statutes for agritourism

- Easing environmental health requirements for small-scale non-potentially-hazardous food processing

- Cross-county standardization of interpretation and enforcement of state regulations

- Create partnerships with state agencies including the CDFA Division of Fairs and Expositions to promote agricultural education and use by farmers and ranchers of county and state fair facilities for mutual benefit

- Foster better connections between agritourism operators and county and state economic development departments

- Create educational materials and help educate city, county and state government staff, elected officials, chambers of commerce, convention and visitor bureaus, etc., about agritourism

- Organize a statewide agritourism promotion campaign/brand which supports regional branding campaigns

- Provide staff to coordinate all these activities and to maintain communications among all those involved in California agritourism

Potential obstacles and issues facing the formation of a statewide agritourism organization were also brought up in the group discussions:

- Defining and explaining organization’s benefits and value to potential members

- Recognizing and working with the limits to farmers’ time to participate

- Funding the organization while keeping membership affordable

- Recognize the need for state unity vs. the need for county regulatory autonomy

- Defining agritourism

- Deciding on and defining organization’s priorities

- Maintaining membership control of organization

What's next?

The UC Small Farm Program, working with the UC ANR-based Agritourism and Nature Tourism Workgroup and other partners, is committed to helping coordinate further discussion among everyone involved in California agritourism about the next steps for building effective statewide support.

The summit organizers, in cooperation with representatives from interested state agencies and organizations, are preparing a white paper to explore the potential process for organizing a statewide agritourism association in California.

Formation of a statewide organization might begin with agreement on a sponsoring agency for a start-up group, would need start-up funding, and would involve wide discussion with potential membership about needs, issues and organizational structure.

Read more:

Presentations, handouts, and small group reports from the summit are available on the UC Small Farm Program’s website. Summit participants also received contact information for participants who agreed to share their information, in order to better facilitate networking and communication.

Back to the newsletter: Find more Small Farm News articles from our Vol 1. 2012 edition.

Selling to chefs, wholesale at a farmers market

Though growers can earn retail prices at farmers markets, many farmers find their profits challenged by the additional marketing costs required, such as transportation and staff time. But one farmers market has developed a way that it can help farmers sell higher volumes to multiple buyers with just one trip — by serving as a venue for sales to restaurants and wholesale distributors, in addition to individual customers.

The Santa Monica Farmers Market hosts 75-80 farmers every Wednesday and could very well be the nation's largest "wholesale farmers market." Laura Avery, farmers market manager, gave a presentation about sales to chefs and professional produce buyers at the California Small Farm Conference.

"We allowed it to progress organically," Avery said. "This happened by itself — just people doing what they want to do and getting what they want to get."

She said that a recent survey of professional produce buyers at the market found that they shop for 5-25 customers each week and have been sourcing from the market for 5-15 years. They reported average produce sales of $1,000 to $4,000 each week from the farmers market.

In one of its few concerted efforts to facilitate these sales, the market has designated parking for chefs and produce companies. Avery said some of the trucks will load up and return multiple times over the market's four hours.

A grower's perspective

Jerry Rutiz has been selling to restaurants at the Santa Monica Farmers Market for 29 years. He grows vegetables, berries and flowers on 28 acres in Arroyo Grande and also operates a CSA and farm stand.

"About 70 percent of what we bring to the farmers market is sold to restaurants," Rutiz told conference participants.

He provided some tips for farmers who want to sell to restaurants and develop relationships with chefs.

"Ask the chef what he wants or can't get," Rutiz said. "Don't expect to sell cabbage or white cauliflower to a restaurant, but if you can bring purple, orange or green cauliflower — that can differentiate you and can help differentiate their restaurant from other restaurants."

Also: "Restaurant prices have no consequence with wholesale prices of the moment," he said. "Price is not the biggest criteria, quality and consistency are."

Though Rutiz has found success with chefs, restaurant sales aren't the focus of all farmers at the Santa Monica market.

"We figure about 25 percent [of produce sold at the Wednesday market] is restaurant wholesale," Avery said. "Some farmers like Jerry sell a majority to restaurants, but some sell just to customers and not to restaurants."

Complications

"This is enterprise that takes place on the sidewalk behind the trucks, not in front of the tables where the public buys," Avery said.

Sales to distributors must adhere to wholesale size and pack regulations, though recent state legislation (AB 2168) allows chefs and restaurants to purchase exempt produce directly from farmers.

Rutiz said complications can arise if, for example, a restaurant agrees to buy all of a particular product — the same product that a traditional farmers market customer wants to buy from him.

"The trick is to cover up the produce [that's already sold] or leave it up in the truck. Or have a little stash of strawberries on the side and act like you're doing them a favor," he said.

What it means for buyers

The topic of farmers markets as a venue for wholesale produce buyers came up during another workshop at the conference as well. Karen Beverlin, vice president of specialty sales for FreshPoint, said her company buys from 28-35 farmers every Wednesday in Santa Monica.

"Farmers markets are huge for our company to meet small farmers," Beverlin said. "It's really helped us basically be an aggregator … and meet farmers who we might not have otherwise met."

As a market manager, Avery sees these additional sales at the market as another means of facilitating sales between farmers and consumers.

"The impact of the restaurants and produce companies is we have now established sales levels consistently that are as high as the highest day used to be," Avery said. "The bottom line is we're trying to get the product from the farm to the customer at a good price."

Advice for farmers market managers

For growers and market managers who are interested in developing their farmers markets as a hub for chefs and professional buyers, Avery offered these additional tips:

- Encourage your local media to do a story about a farmer and a chef who shops at the market.

- Understand from chefs which day(s) they need to shop and direct them to the closest market on that day.

- Encourage farmers to produce an availability list that they can email out to chefs on a weekly basis.

- Talk to produce companies about a restaurant that you know might be interested in farmers market produce, and encourage the produce company to drop off samples at the restaurant. This can lead to follow-up orders.

Back to the newsletter: Find more Small Farm News articles from our Vol 1. 2012 edition.

Tips for growing, selling organic

California growers considering organic certification were able to hear about the value of doing so — and tips for getting started — from a farmer, buyer and agricultural economist at one of the California Small Farm Conference workshops.

“I had about a thousand customers per week at the farmers market, pulling up my carrots and saying, ‘Are these organic?’ And I got tired of that question,” said farmer Phil McGrath, about one of the many reasons he chose to grow organically.

McGrath and a produce buyer he works with both talked about the importance of “telling your production story” as a marketing tool, and said having the certified-organic label helped.

“We feel that it’s easy for consumers to wrap their heads around ‘organic.’ They think they know what it means,” said Karen Beverlin, vice president of specialty sales for FreshPoint. “The labels give us something to hang on [McGrath] and his product, but then it's up to us to tell the story of how that's so different.”

One of the things that sets McGrath apart from some other farmers is his emphasis on diversified farming. His main piece of advice for budding organic farmers is growing organically is easier on a diversified farm. McGrath Family Farms grows mixed vegetables, strawberries, heirloom tomatoes, pumpkins and cover crops.

“If you're going to be an organic farmer, it's hard to grow just one thing,” he said. “It’s a kick to be this diversified – it really does make you a stronger farmer. I grow more things in season, I use a normal amount of water and I’ve stabilized my labor demands. I have very few pest problems; probably my first [main pest] would be birds, next would be mammals.”

Karen Klonsky, UC Cooperative Extension agricultural economist at UC Davis, explained the basics of organic certification and the organic market.

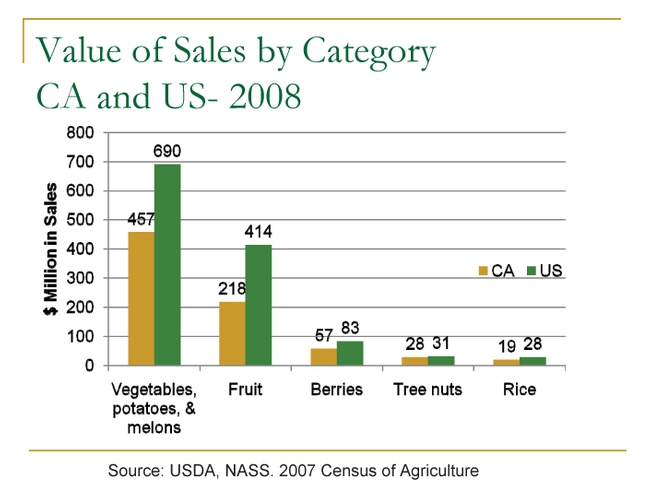

“California dominates organic production nationwide,” she said.

Organic production includes following USDA’s National Organic Program, with no prohibited substances for at least three years — including synthetic substances not on the national list, genetic engineering and sewage sludge. Farmers selling more than $5,000 per year must be certified to call their produce organic. The process to get certified involves preparing an organic system plan, recordkeeping and an annual inspection. Klonsky explained that there are 25 USDA accredited certifiers active in California.

“All of the rules being followed are the same by any certifier,” she said. “How they do differ is whether they’re nonprofit, for-profit, a government agency, etc.”

Though costs and fee structures vary, all of the certifiers charge for the application, inspection and certification. Some certifiers also have trade associations, play political roles, offer educational programs or have specialized services and expertise.

Klonsky said that growers should plan for the certification process to take 8-12 weeks, though many certifiers offer expedited programs at an additional cost.

“That's something to ask a certifier: Once I get you my paperwork, how soon until you'll visit my farm and I'll be certified?” Klonsky said.

The certifier’s inspection will review and verify your farm’s organic system plan (OSP), with a facility tour including any storage and processing, all records pertaining to organic production and practices and an audit trail with a balance of inputs and outputs.

Klonsky recommends setting aside time, work space and relevant staff members for the inspection. Any changes to labels or systems should be submitted to the certifier prior to the inspection, to save time and confusion. (View Klonsky's presentation and others from the conference.)

Resources recommended by Klonsky:

- ATTRA, the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service provides information for organic production, marketing, databases, and certification information

- The Organic Trade Association works with U.S. organic industry to support and grow organic.

- The National Organic Program has monthly reports, policy updates, list of U.S. certifiers

- CDFA Organic Program has information on registration, cost share for certification and accredited certifiers in California

- Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) is the U.S. gold standard for materials review and information

Back to the newsletter: Find more Small Farm News articles from our Vol 1. 2012 edition.

CSA operators offer tips

With the growing popularity of community supported agriculture has come a proliferation of CSA models, with a wide variety of structure, goals, customer interactions and food products. Two different CSAs offered tips to farmers and workshop participants at the California Small Farm Conference.

On the panel were John Fonteyn and Elizabeth Del Negro, who operate Rio Gozo Farm in Ojai on 3.5 leased acres as the sole employees.

Also on the panel was Sarah Nolan, the CSA coordinator for South Central Farmers Cooperative, which farms 85 acres in Buttonwillow and delivers to locations throughout the Los Angeles basin.

“I think it’s important that we focus on the community aspect of community supported agriculture,” Fonteyn said. “I didn’t want to just put food in boxes and put them in trucks and send them away. I really wanted to live in a community.”

He believes that many CSA member also seek a sense of community and want to be part of building that community themselves. Many of their CSA members volunteer to pack boxes and visit the farm at other times too.

Fonteyn thinks that being likeable as a business person and farmer can go a long way.

“People go to you because they like you,” he said. “It’s really an attachment to us, our goals, our approachability.”

They also make concerted efforts to stay in the public eye.

“We say yes as often as we can,” Del Negro said, listing on-farm dinners, fundraisers, partnering with chefs and entertainers, speaking at events, providing farm tours and cooperating with media members as things they “say yes” to in order to maintain a strong community presence.

Rio Gozo also has an online presence, through a blog, Facebook and Twitter.

“When people search for farms, they want to see beautiful images,” Del Negro said. “When you go on our website, you’ll see deep colors, sharp photos and very few words.”

Retention

Rio Gozo initially offered monthly, seasonal and annual memberships, but have shifted away from offering monthly subscriptions — which has increased their membership retention.

The South Central Farmers Cooperative offers boxes on a one-time basis, in addition to offering monthly and seasonal subscriptions. Though they deliver about 300 boxes per week, they have about 500 customers per year receiving a box at one time or another.

“A lot of your work as a CSA is to throw that broad net out to get more people,” Nolan said. She described a 60 percent attrition rate for CSAs on average as normal.

But, she said, it’s also important to form relationships with customers, so that people who might be inclined to continuing their membership with the CSA do indeed stay on.

Since the South Central Farmers Cooperative also sells at farmers markets, Nolan said they make a point of trying to help customers self-assess whether a CSA is right for them.

“[Consumers] need to figure out — are you a CSA person or a farmers market person?” she said.

Planting

They each offered these general tips about what to grow:

- “Plant as many varieties as possible because CSA members want variety in their boxes, and if you’re not aggregating, then you need to grow it,” Del Negro said.

- “We try to grow as much as possible on our own farm,” Nolan said. “We do partner with other farms and we are very clear with CSA members about who we’re partnering with and what’s going on.”

Regulation

Dave Runsten, of Community Alliance with Family Farmers, spoke up to explain that the California Department of Food and Agriculture is currently working on issues related to direct marketing, including CSAs and how CSAs relate to food safety.

One of the concerns discussed related to food safety for CSAs is controls for “potentially hazardous foods,” which is a regulatory term that can refer to food products that cannot be safely held without temperature controls.

“So the extent that you don’t include potentially hazardous foods in your CSA box, then you won’t be subject to those handling requirements,” Runsten said.

Other concerns related to food safety and CSAs might include the CSA boxes themselves, whether they are cleaned or use a liner, and traceability of product through CSA channels.

Runsten said he maintains an email list of CSA operators in California, as a source for advice and opinions. CAFF is also planning a conference focused on CSAs in January 2013.

Back to the newsletter: Find more Small Farm News articles from our Vol 1. 2012 edition.